I. Discovery

I believe I can pin down the exact date that I began to make my way out of the maze. It was Saturday, March 17, 2018.

I can’t fathom what compelled me to take acid on Saint Patrick’s Day. I was in my friend’s room. I was nineteen. The only thing I remember about those moments as we waited for the last member of our group to show was staring at the lampshade and the calendar on the wall.

By the time we got out of the cab at the party, I was already losing my grip. I was holding together just fine, but that infinitely-up-to-interpretation-ness of social interaction was already rearing its terrifying head.

Once inside, I was as incapable of communication as I had been at fourteen years old. My consciousness seemed to detach itself from the LLM I had built inside of my mind allowing me to watch it operate from a distance.

For the first time, I saw the autonomic machinery that constructed my sentences from moment to moment. This unnatural awareness was terribly disruptive. It brought these mechanisms into startling self-awareness causing them to trip over themselves.

Some intelligence which seemed strangely ahead of my conscious mind — more like superconscious than subconscious — would construct a kind of proto-sentence out of ideogrammatic “blocks.” The best thing I can liken this to is a “mad lib” made entirely of blanks. A series of approximate intimations sequenced in a particular order.

After this, a second intelligence with which “I” more readily identified would rush to fill in the blanks with actual language. Strangely, it did not do this by chaining words together. It would instead curate a sequence of quotations. Fragments of statements made by others in a vast archive of soundbites. These I would string into a composite whole, then modulate my delivery as needed.

Everything I just described was almost purely reflexive activity like walking. It filled spaces made of milliseconds. It was too fast to notice in a sober state of mind.

Nonetheless, I did see what was happening, because I recognized the elements in this soundbite inventory. I could tell word by word who I was quoting. In some instances, I could even recall in a fraction of a second the exact time and context in which I heard the fragment I was using. They were tiny, versatile units of speech borrowed from other people. There was a lot of Jordan Peterson, Joe Rogan and various comedians at that time. I knew they were quotations because I wasn’t just borrowing the “what” that was said, but also the “how” which was often very recognizable.

These fragments were things like Joe Rogan’s: “it’s entirely possible“ and “a buddy of mine.” I call them “glossalisms.” Distinct, recurring units of speech which are reflexively used as cohesive phrases.

There was obviously some actual improvisation, but it was surprisingly sparse. This seems strange at first, but if you think about it: why would you remember words more readily than patterns of speech? You need to build sentences in fractions of a second. Why would you start from scratch if you have access to fully functional phraseology that’s already been socially tested? It would be grossly inefficient and unnecessarily risky to build every statement from the ground up. Why reinvent the wheel?

A glossalism functions as a highly adaptable linguistic element, reducing the need for improvisation, and thus conserving cognitive resources. They can also serve to signal in-group membership. We already know that accents, slang and other linguistic signatures serve this function. Shared glossalisms would be understood faster than whole new phrases, so they would accelerate in-group communication as well.

It’s certainly strange to be aware of this, but I find it hard to believe that I’m some kind of anomaly in this respect. It just makes sense to do it this way, and our patterns of speech are far too consistent to imagine that we don’t. The cautious alteration of existing structures over time is mother nature’s preferred mode of innovation.

I suppose it was visible to me because I learned these skills so late. I was not socially fluent until the end of my adolescence. I developed normal communication skills by studying thousands of hours of conversation and banter on the internet, so the manner of my expression was relatively new, quite artificial and abnormally deliberate.

Of course, glossalisms vary in their rigidity and flexibility, and the use of them can be more or less inventive, but to not use them at all just isn’t economical.

This of course is nothing more than a microcosm of an oral tradition. It is a living archive of the most memorable and effective units of meaning. Another advantage is that since the mechanism is memory, the process would favor more memorability. Less memorable glossalisms would be less likely to be used. Your speech would benefit from this by being highly adapted to the structure of memory.

This manner of speaking would explain the very common experience of knowing what you want to say but not being able to say it. Intention and articulation correspond to independent and imperfectly aligned systems. It’s Plato’s demiurge using the forms as a reference but not getting it quite right.

If you’re still skeptical, I would point to online communication which today leans heavily on the use of memes — particularly “reaction images” and gifs. I would argue this is an ossified and degenerated form: clunky stock responses rather than granular rudiments and fluid improvisation. But nonetheless, this pathologized form is probably the result of atrophy, not innovation. Letters devolving back into cave art.

Speech then consists of memetically propagating structures of verbal patterning remixed and hybridized again and again by a supervenient hierarchy of reflexes.

Though I didn’t know it yet, understanding what exactly speech was would open doors to things not yet imaginable.

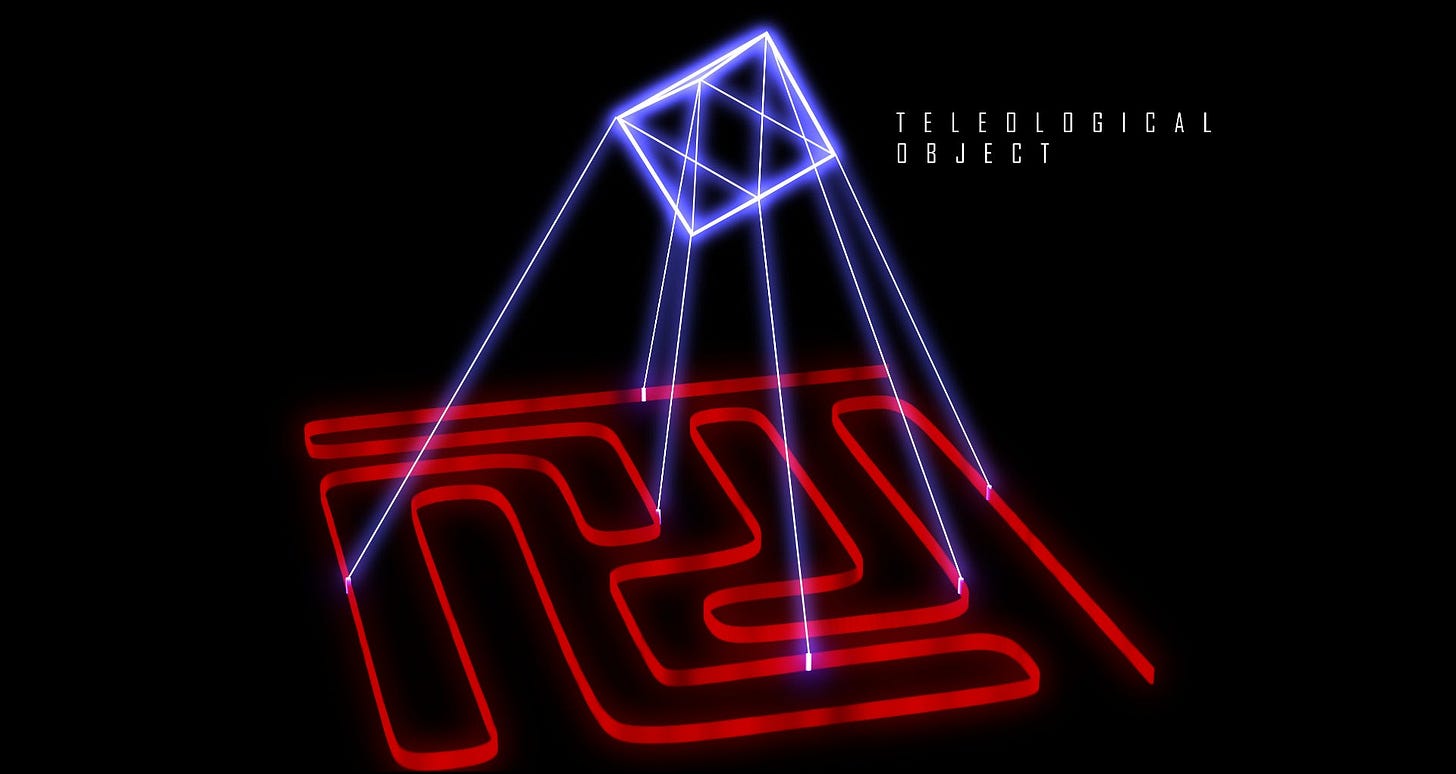

II. Mazes

“…Yet something was familiar. This person was very much like the one I was maybe six or seven years ago, and the world he perceived was the same matrix of simulacra which I had lived in back then…”

“…in the maze, my environment reminded me of movies, TV shows and video games, and I had been trying to grasp my reality as if it were like those instead of like mythology. Consequently, I almost never grasped it…”

The sentence assembly system I described relies on a vast abyssal memory archive of glossalisms which inherits its associational structure from a semiotic taxonomy.

Each psychoglyph represents a category of glossalisms organized around a theme.

The same principle holds true in perception. December 21, 2022, the night I first saw the maze, was just the rediscovery of the same structure, but with something even more fundamental: thought itself.

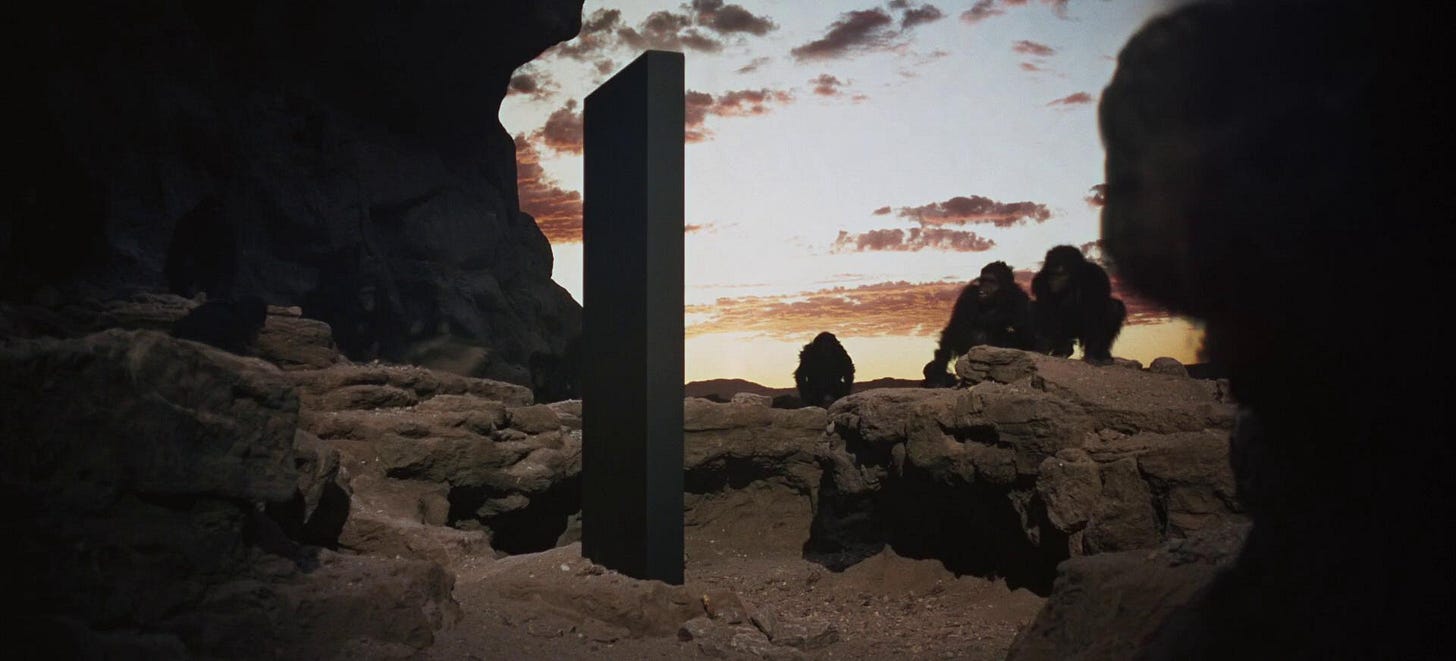

A media archetype or storytelling trope is also a kind of glossalism, and such noetic glossalisms are what you use to see and think. What then might be the consequences if we begin to derive them from simulacra, illusion and escapist flights of fancy?

The purpose of narrative is to compact reality into representational instruments of thought. Our stories today, by and large, are no longer doing this.

All fictions are some admixture of parable, propaganda and pornography. The parable, distinguished by its fidelity and integrity (the quality of being integrated), is today, unfashionable. The average information diet consists almost entirely of the other two. You’ve certainly seen the results of this. We know what is meant when it is said that someone has been “watching too many movies.”

You and I have both seen people who use video game logic in real life. Who have pornographized their sexuality. Who can’t express a genuine emotion without “TV acting.” Who can’t conceive of a higher ideal than “make money, get bitches.” But the internalities of this kind of condition are far more troubling and insidious.

There are certain peculiar folk — often maladjusted outcasts — who emote like anime characters. If you listen to the way they frame their experiences and narrativize their lives, it becomes apparent that this kind of speech is just a symptom of something much deeper. These people perceive the world as if it consisted of the same narrative blocks and rhythms as an anime.

The problem should be obvious: reality does not remotely resemble an anime.

I played video games for much of my childhood, but stopped at the age of fifteen. Even so, my dreams continued to have “video game physics” into my early twenties. My mother told me once that she dreams in black and white. This was once the norm.

The research conducted in the early 20th century unanimously concluded that the vast majority of people dream in black and white. For example, Bentley (1915) reported that 20% of dreams contain colour...

…The proportion of people reporting coloured dreams even decreased in the 1950’s: Knapp (1956) claimed that as little as 15% of dreams contain colour, while Tapia, Werboff, and Winokur (1958) found that only 9% of people who reported to a hospital in St. Louis for non-psychiatric medical problems remembered having coloured dreams. Moreover, this figure was contrasted with a 12% rate of reporting coloured dreams among psychiatric inpatients in the same hospital and the researchers concluded that vivid and coloured dreams may be a sign of psychological problems. Overall, researchers and study participants agreed that black and white dreams were the norm, and rare cases of coloured dreams were dubbed ‘Technicolor’ dreams (Calef, 1954, Hall, 1951), highlighting their perceived artificiality.

From: Do we only dream in colour? A comparison of reported dream colour in younger and older adults with different experiences of black and white media

To watch a film, listen to a song or even read a book is a form of mystical experience. It is the technological actuation of an altered state to induce a visionary journey. To primal man whose perception is generally more honest than our own, the difference between a drama and a dream is mostly circumstantial.

Ritual is the common ancestor of all representational experience. Storytelling, singing, dancing and artistry all trace their origins back to ritualism.

The link between media and dreams reveals the function and essence of the former to be sacramental. The purpose of sacrament is to influence the unconscious. This is probably what intuitions about “predictive programming” are gesturing at.

Modernity is a movie, a ritual and a dream (or simulation) all at the same time.

The problem with the majority of our media today is that it seems to exist purely for its own sake. It does not serve a purpose higher than itself. Imitate the protagonist of a modern love story and you will be less likely to find love. Imitate the funniest character in a comedy and you will be supremely irritating. Try out some moves you saw in an action film and you’ll get beat up.

But psychotoxicity penetrates far beyond such superficialities, right down into the “glossalisms” of perception. These control how you solve problems, because they inform what “problems” are and why they are problems in the first place. They define the relationships between experiences and information and the way attention moves from one thing to another.

You have an inventory of stock narrative schemas, just like stock speech patterns. For a simple, but tactile example, consider this horror movie trope:

I close the medicine cabinet and see the killer behind me in the mirror.

There is a near zero chance of this ever happening in real life. But it’s memorable enough to inspire persistent phobias and superstitions. The instinct to look behind you before you close the medicine cabinet is a reflex. Regardless of whether you have that particular reflex or even think it matters, there is an entire industry that exists solely to access and engineer such associations: it’s called marketing.